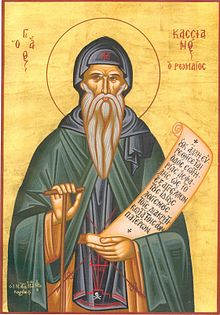

John Cassian

Saint John Cassian (ca. 360 – 435 AD) was a Christian theologian celebrated in both the Western and Eastern Churches for his mystical writings. He is known both as one of the "Scythian monks" and as one of the "Desert Fathers."

Quotes

[edit]Institutes of the Coenobia (c. 420 AD)

[edit]Our third conflict is against covetousness which we can describe as the love of money; a foreign warfare, and one outside of our nature. ... For the rest of the incitements to sin planted in human nature seem to have their commencement as it were congenital with us, and somehow being deeply rooted in our flesh, and almost cœval with our birth, anticipate our powers of discerning good and evil, and although in very early days they attack a man, yet they are overcome with a long struggle.

But this disease coming upon us at a later period, and approaching the soul from without, as it can be the more easily guarded against and resisted, so, if it is disregarded and once allowed to gain an entrance into the heart, is the more dangerous to every one, and with the greater difficulty expelled. For it becomes "a root of all evils" [1 Timothy 6:10] and gives rise to a multiplicity of incitements to sin.

- Book VII, "On the Spirit of Covetousness," Chapter I

- Some faults grow up without any natural occasion giving birth to them, but simply from the free choice of a corrupt and evil will, as envy and this very sin of covetousness; which are caught (so to speak) from without, having no origination in us from natural instincts. But these, in proportion as they are easily guarded against and readily avoided, just so do they make wretched the mind that they have got hold of and seized, and hardly do they suffer it to get at the remedies which would cure it.

- Book VII, Chapter V

- Having laid the foundations badly, they [covetous souls] are unworthy to raise an edifice of virtue and reach the summit of perfection.

- Book VII, Chapter V

- With the increase of wealth the mania of covetousness increases.

- Book VII, Chapter VII

- Gold and the love of gain become to him his god, as the belly does to others. Wherefore the blessed Apostle, looking out on the deadly poison of this pest, not only says that it is a root of all kinds of evil, but also calls it the worship of idols, saying "And covetousness (which in Greek is called φιλαργυρία) which is the worship of idols." [Colossians 3:5] You see then to what a downfall this madness step by step leads, so that by the voice of the Apostle it is actually declared to be the worship of idols and false gods, because passing over the image and likeness of God (which one who serves God with devotion ought to preserve undefiled in himself), it chooses to love and care for images stamped on gold instead of God.

- Book VII, Chapter VII

- It is an impossibility for him who, overcome in the matter of a small possession, has once admitted into his heart a root of evil desire, not to be inflamed presently with the heat of a still greater desire.

- Book VII, Chapter XXI

- We must not only guard against the possession of money, but also must expel from our souls the desire for it. For we should not so much avoid the results of covetousness, as cut off by the roots all disposition towards it. For it will do no good not to possess money, if there exists in us the desire for getting it.

- Book VII, Chapter XXI

- It is possible that those who are in no way pressed down with the weight of money may be condemned with the covetous in disposition and intent. For it was the opportunity of possessing which was wanting in their case, and not the will for it.

- Book VII, Chapter XXII

- How will he see to cast out the mote from his brother's eye, who has the beam of anger in his own eye?

- Book VIII, Chapter V

- Wrath that is nursed in the heart, although it may not injure men who stand by, yet excludes the splendour of the radiance of the Holy Ghost, equally with wrath that is openly manifested.

- Book VIII, Chapter XII

Sometimes when we have been overcome by pride or impatience, and we want to improve our rough and bearish manners, we complain that we require solitude, as if we should find the virtue of patience there where nobody provokes us: and we apologize for our carelessness, and say that the reason of our disturbance does not spring from our own impatience, but from the fault of our brethren. And while we lay the blame of our fault on others, we shall never be able to reach the goal of patience and perfection.

The chief part then of our improvement and peace of mind must not be made to depend on another's will, which cannot possibly be subject to our authority, but it lies rather in our own control. And so the fact that we are not angry ought not to result from another's perfection, but from our own virtue, which is acquired, not by somebody else's patience, but by our own long-suffering.

- Book VIII, Chater XVI

Conferences of the Desert Fathers (c. 420 AD)

[edit]- Ramsey, Boniface (trans.) (1997). Cassian: The Conferences. Ancient Christian Writers no. 57. New York: Newman Press.

- The holy person ... when, raised up from the earth, he contemplates all present and earthly realities as mere smoke and an empty shadow and disdains them as soon to disappear;

when, with ecstatic mind, he not only ardently desires future realities but even sees them with clarity;

when he is effectively fed by spiritual theoria;

when he sees unlocked to himself the heavenly sacraments in all their brightness;

when he sends prayers purely and swiftly to God;

and when, inflamed with spiritual ardor, he passes over to invisible and eternal realities with such utter eagerness of soul that he cannot bring himself to believe that he is in the flesh.- pp. 224-225, 6.10.2

- Yet sometimes the mind which advances to that true disposition of purity and has already begun to be rooted in it, conceiving all of these at one and the same time and rushing through them all like a kind of ungraspable and devouring flame, pours out to God wordless prayers of the purest vigor. These the Spirit itself makes to God as it intervenes with unutterable groans, unbeknownst to us, conceiving at that moment and pouring forth in wordless prayer such great things that they not only—I would say— cannot pass through the mouth but are unable even to be remembered by the mind later on.

- p. 339, 9.15.2

- This prayer, then, although it seems to contain the utter fullness of perfection inasmuch as it was instituted and established on the authority of the Lord himself, nonetheless raises his familiars to that condition which we characterized previously as more sublime. It leads them by a higher stage to that fiery and, indeed, more properly speaking, wordless prayer which is known and experienced by very few. This transcends all human understanding and is distinguished not, I would say, by a sound of the voice or a movement of the tongue or a pronunciation of words. Rather, the mind is aware of it when it is illuminated by an infusion of heavenly light from it, and not by narrow human words, and once the understanding has been suspended it gushes forth as from a most abundant fountain and speaks ineffably to God, producing more in that very brief moment than the self-conscious mind is able to articulate easily or to reflect upon. Our Lord himself represented this condition in similar fashion in the form of those prayers that he is described as having poured out alone on the mountain and silently, and when he prayed in his agony he even shed drops of blood as an inimitable example of his intense purpose.

- pp. 345-346, 9.25.1

- But they alone see his Godhead with purest eyes who,

mounting from humble and earthly tasks and thoughts,

go off with him to the lofty mountain of the desert which,

free from the uproar of every earthly thought and disturbance,

removed from every taint of vice,

and exalted with the purest faith and with soaring virtue,

reveals the glory of his face and the image of his brightness to those who deserve to look upon him with the clean gaze of the soul.- p. 375, 10.6.2

- For the rest, Jesus is also seen by those who dwell in cities and towns and villages—that is, by those who have an active way of life and its obligations—but not with that brightness with which he appears to those who are able to climb with him the aforesaid mount of the virtues—namely, to Peter, James, and John. For it was in the desert that he appeared to Moses and spoke to Elijah.

- p. 375, 10.6.3

- This will be the case when every love, every desire, every effort, every undertaking, every thought of ours, everything that we live, that we speak, that we breathe, will be God, and when that unity which the Father now has with the Son and which the Son has with the Father will be carried over into our understanding and our mind, so that, just as he loves us with a sincere and pure and indissoluble love, we too may be joined to him with a perpetual and inseparable love and so united with him that whatever we breathe, whatever we understand, whatever we speak, may be God.

In him we shall attain, I say, to that end of which we spoke before, which the Lord longed to be fulfilled in us when he prayed: ‘That all may be one as we are one, I in them and you in me, that they themselves may also be made perfect in unity.’ (John 17:22-23)- pp. 375-376, 10.7.2

- Not without reason has this verse [Psalms 70:1] been selected from out of the whole body of Scripture. ... ‘O God, incline unto my aid.’ ... This verse should be poured out in unceasing prayer so that we may be delivered in adversity and preserved and not puffed up in prosperity. You should, I say, meditate constantly on this verse in your heart. You should not stop repeating it when you are doing any kind of work or performing some service or are on a journey. Meditate on it while sleeping and eating and attending to the least needs of nature. This heart’s reflection, having become a saving formula for you, will not only preserve you unharmed from every attack of the demons but will also purge you of every vice and earthly taint, lead you to the theoria of invisible and heavenly realities, and raise you to that ineffably ardent prayer which is experienced by very few. Let sleep overtake you as you meditate upon this verse until you are formed by having used it ceaselessly and are in the habit of repeating it even while asleep.

- pp. 379, 382-3; 10.10.3,14-15

- Thus we shall penetrate its meaning not through the written text but with experience leading the way. So it is that our mind will arrive at that incorruptible prayer to which, in the previous discussion, as far as the Lord deigned to grant it, the conference was ordered and directed. This is not only not laid hold of by the sight of some image, but it cannot even be grasped by any word or phrase. Rather, once the mind’s attentiveness has been set ablaze, it is called forth in an unspeakable ecstasy of heart and with an insatiable gladness of spirit, and the mind, having transcended all feelings and visible matter, pours it out to God with unutterable groans and sighs.

- p. 385, 10.11.6

- For there is no one who does not know from the vastness of creation itself that the works of God are marvelous. But what he accomplishes in his holy ones by his daily activity and abundantly pours into them by his particular munificence—this no one knows but the soul which enjoys it and which, in the recesses of its conscience, is so uniquely the judge of his benefits that it cannot only not speak of them but cannot even seize them in understanding or thought when, leaving behind its fiery ardor, it falls back to gazing upon material and earthly realities.

- p. 450, 12.12.2

- Let me pass over those secret and hidden dispensations of God which each holy person’s mind sees operative in a special way within itself at given moments;

over that heavenly inpouring of spiritual gladness by which the downcast mind is uplifted by an inspired joy;

over those fiery ecstasies of heart and the joyful consolations at once unspeakable and unheard of, by which those who occasionally fall into a listless torpor are raised as out of the deepest sleep to the most fervent prayer.- p. 451, 12.12.6

- It is inevitable that the mind which does not have a place to turn to or any stable base will undergo change from hour to hour and from minute to minute due to the variety of its distractions, and by the things that come to it from outside it will be continually transformed into whatever occurs to it at any given moment.

- V

- Wherefore a monk's whole attention should thus be fixed on one point, and the rise and circle of all his thoughts be vigorously restricted to it; viz., to the recollection of God, as when a man, who is anxious to raise on high a vault of a round arch, must constantly draw a line round from its exact centre, and in accordance with the sure standard it gives discover by the laws of building all the evenness and roundness required....

- VI